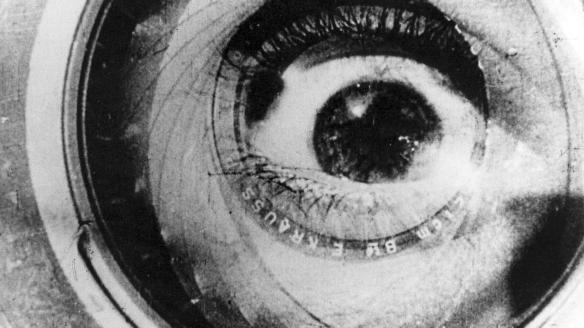

A popular observation made about silent films was that they had reached their pinnacle by the time sound was introduced. Recently watching Dziga Vertov’s avant-garde Man with a Movie Camera, it’s hard to argue with such a case. Often found on countless “greatest movie” lists, this culmination of the “city documentary” genre exceeds in just about every boundary imaginable. As Soviet montage formalism, Man’s impressive in its seamless control of actuality and subjectivity. As nationalistic propaganda, it deviates from shoving any set of rigid ideals and focuses exclusively on people behaving like people, effectively delivering its patriotic statement across humanistically. As a silent film overall, it tells the story of a whole nation without a single intertitle. Add to it its ingenius use of self-reflexivity—allowing to see a day in a life of an unnamed city and then watching as, brace yourself, the editor pieces the film for us to watch as an audience in the actual movie, and you’ve got a master at hand orchestrating a well-maneuvered requiem to a medium we had already bid farewell to. So at #1 Man with a Movie Camera goes.

1. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov)

2. Un chien andalou (Luis Buñuel)

3. Blackmail (Alfred Hitchcock)

4. Lucky Star (Frank Borzage)

5. A Cottage on Dartmoor (Anthony Asquith)

6. Pandora’s Box (G.W. Pabst) and Diary of a Lost Girl (G.W. Pabst)

7. Hallelujah (King Vidor)

8. The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch)

9. Spite Marriage (Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton)

10. The White Hell of Pitz Palu (Arnold Fanck and G.W. Pabst)

You want to talk about unprecedented, Luis Buñuel did to experimental movies in less than twenty minutes what few—if any artists in that vein—could claim in a career’s lifetime. Then there are those films that treaded the line between silence and sound. I’ve had the fortune of watching Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail on the big screen with Anny Ondra driven mad by the word “knife.” It is said that a silent version of the film exists, but I can’t imagine its delivery being just as impactful. A Cottage on Dartmoor mirthfully plays with a scene mocking sound at a movie theater. But other than that, Asquith’s glum thriller is anything but playful. Vidor’s Hallelujah and Lubitsch’s The Love Parade take leaps by becoming some of the very first musicals in film. All the while, directors like G.W. Pabst and Frank Borzage presented works that were nothing less than masterpieces of the silent movement.

Those titles that just missed the ranks include a twofer from Dudley Murphy: Both St. Louis Blues and Black and Tan are nothing short of exceptional in conveying just what exactly the blues and jazz meant respectively at the time—not to mention becoming cinematic benchmarks on music history by preserving in film the enigmas that were Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington. Erich von Stroheim had his problem picture, Queen Kelly, with Gloria Swanson taking control midway and unfortunately losing the film’s focus; and The Marx Brothers debut was forever embedded in nitrate with The Cocoanuts. Notable performances—apart from Louise Brooks cementing a mother of a legacy in one year alone—include Helen Morgan in Rouben Mamoulian’s remarkably fluid Applause, Anna May Wong overseas in E.A. Dupont’s Piccadilly, and Gary Cooper in Victor Fleming’s Wolf Song and The Virgininan; my argument for the latter being that while Cooper wasn’t the most versatile actor around, he had the aura of what I always found myself to believe was a true movie star. So… there you go.

Next time: 2006.