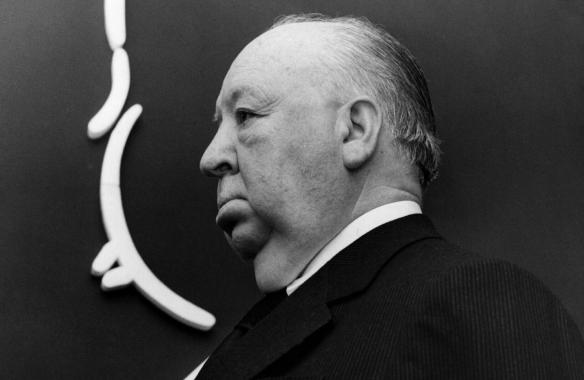

It was Alfred Hitchcock’s birthday last week, so I thought this would be a great opportunity to recommend two titles from his impressively prolific body of work. Apart from the all too familiar hallmarks (Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho), Alfred Hitchcock had a broader cannon of lesser-known films—and that’s a relative statement to make since Hitchcock movies aren’t necessarily thought of as “overlooked”—that have more than earned their keep and due.

I’m specifically talking about his 1940s period. His ’50s stride of greatest hits lose a certain kind of intimacy that has made his earlier work feel less like magazine gloss and more immediate, personal. His mid-to-late ’50s output generally becomes lighter fare, too—à la Mad Men style in its urbanite poshness. Hell, I personally like to think of this latter period as “Metropolitan Hitch.” Tacky, I know.

But, anyway, his films of the 1940s have a raw, fatalistic edge. And like the black smoke cloud that blots out the picturesque sky when Uncle Charlie arrives at Santa Rosa in Shadow of A Doubt, these films cast a seed of malevolence over small-town American idealism, insidiously spreading in corroboration with war-time disenchantment and soon-to-be shell-shock trauma. Strangers on a Train (1951), I, Confess (1953) and The Wrong Man (1956) are certainly a continuation of this nature, but, by then, Hitchcock—like most artists of his longevity—had long undergone a different aesthetic route. The rest, as they say, is history.

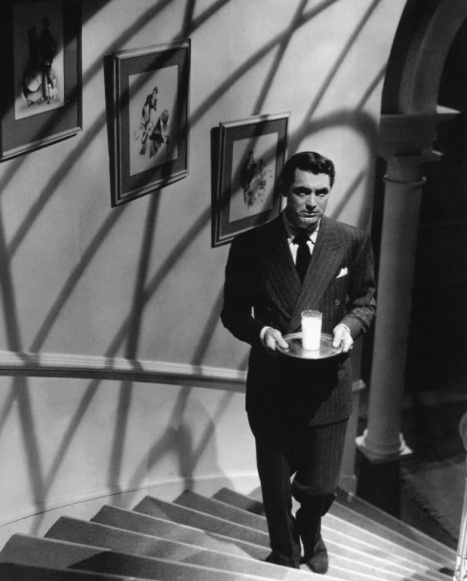

Released by RKO pictures in 1941, Suspicion is the only film where Hitchcock directed an actor to an Academy Award-winning performance. Joan Fontaine, who had just come off of playing the lead in another Hitchcock dog-ear, Rebecca, stars as Linda McLaidlaw—because, of course—a frumpish and cowering young lady of substantial financial means set on a steadfast pace toward, and I say this with the mid-Atlantic accent shivers, “spinsterhood.” Cary Grant, an unsurprisingly magnetic rascal, swoons her off her feet and out of her reasonable shoes. So, the idea argued, is that his reckless cad-like spending becomes a small price to pay for the barren life Joan was set to live—we’re talking Moses leading the Israelites to the promise land dry. But when love-drunk Joan begins to suspect that Cary’s motives are not only ulterior, but murderous (!), paranoia sets up residence like pounding down a “SOLD” sign with a sledgehammer.

But, despite what can be described as a run-of-the-mill thriller premise, Suspicion is far too personal and idiosyncratic for neglect. Why? Because as text book analysis on film grammar goes, Hitchcock’s execution is kitchen-clean perfect. In fact, you just can’t get purer in craft. You see, unlike Rebecca, Suspicion has less David O. Selznick frills, which means it’s not burdened by lofty literary clops of hubris; instead, it amplifies the cinematic essentials (editing, sound, lighting) to optimize the narrative’s utmost effect. Seriously, it’s a case worth betting on. And if Psycho made audiences afraid to take a shower in 1960, one can’t help but think what Suspicion would have done to milk sales had the film been just as influential.

Thornton Wilder—best remembered today for Our Town, a play which depicts the life of a small community with all its simplicities and quaint foibles—is exactly the writer needed to enrich Shadow of a Doubt with nefarious irony. Joseph Cotten plays Uncle Charlie, a calculative murderer known as the “Merry Widow Strangler.” He’s a vampire-like heel who contemptuously seeks out embarrassingly rich widows that he charms, deceives, and murders—ambling away with a disdain that drives him like the rest of us need air. But now on the lam and practically cornered by the authorities, Uncle Charlie is forced to return to his childhood home (God, he was a kid once, huh?), desperate to hide out in plain-sight suburbia. Naturally, his sister and her family are perfect bait as bunker refuge. So Uncle Charlie, that man of the world and culture unseen by the likes of the hokey herd citizenry in Santa Rosa, is touted like a king, particularly by his starry-eyed niece named after him—again, nefarious irony. But soon, young Charlie sleuths her way like Nancy Drew after her growing suspicions reveal that her uncle is every bit the devil incarnate. Meanwhile her father—and other folks alike—shoot the hay by speculating what would constitute the perfect murder, ignorant of the byproduct that they have conjured up like a spell from their macabre fantasies.

Despite some of the film’s time-stamped strokes—which could cull an unsparing laugh from an unaccustomed crowd—Shadow of a Doubt works like a machine because, again… it’s Hitchcock. But add the aforementioned Thornton Wilder touch, and you’re presented with facades, subtext and the likes, that chew away at the homespun, happy surface like vermin on the prowl. I mean just thinking about its merits as a layered drama gives me the, uh, frissons: a psychotic, apathetic killer (is there one that isn’t?) who looks like any ordinary civilian, enters the most puritanical and sanctified of institutions: the family. Evil sets foot into God-fearing country where the traffic guards know pedestrians by name and everyone goes to church on Sunday like clockwork. The fact that Shadow of a Doubt also highlights Uncle Charlie as being a part of his niece, completely incinerates Thornton Wilder’s poster image of simple-town nostalgia by arguing that this veneer is nothing more than a deceit, because behind the ice cream truck jingles and the smell of apple pie cooling off by a kitchen window lies the evil that lives in us all. Those rose-colored glasses might—just might—be tinted with blood when you stand back far enough to take a better look. Wilder was sure pulling our leg, wasn’t he? And he was pulling hard.